It seems like you can’t switch

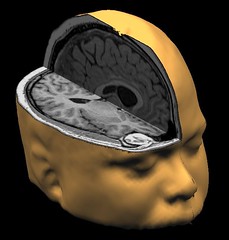

on your TV or open a web browser these days without bumping into brains.

Neuroscientific discoveries are beginning to impact on areas of our lives that

we had thought were set in sociocultural aspic, not in grey and white matter.

It seems like you can’t switch

on your TV or open a web browser these days without bumping into brains.

Neuroscientific discoveries are beginning to impact on areas of our lives that

we had thought were set in sociocultural aspic, not in grey and white matter.

One that particularly interests

me is so-called neuropolitics – ‘the interplay between the brain and politics.’ Using

the word ‘interplay’ (as the Wikipedia definition does) is something of a cop-out,

for we need to face up to the fact that politics happens inside brains, and the

societies we live in are largely created by the repercussions of the actions

that stem from those neural ruminations.

Tempting though it is to brand

the examination of such linkages as pointless ‘neurobollocks’, we cannot continue to view the outcomes of policies as

somehow removed from their sources in the biological brains of those in

positions of power. Obviously, many of us are uncomfortable with the notion

that we might be governed by ‘bad apples’ who, in some cases, we may have

helped to rise to the top. More uncomfortable, though, is the realisation that all

political ideologies are patterns of electrical signals running through the accrued

pathways of their gelatinous substrates.

Does that matter? Couldn’t we

say the same about all human experience? Yes, we could; the key point here is

that the impact on us of the cognitive activity of our leaders in

disproportionate and asymmetrical. They can think us into prosperity, poverty, or oblivion, but

we, as individuals, cannot do the same to them.

I have suggested in a previous

article that we should implement some form of

neurological testing of political candidates, to try, as best we can, to tease

out their true motivations. Saying that you are fit to run a country is an

extraordinary claim – one that, in my opinion, requires extraordinary evidence.

And talking of evidence, what is

all the fuss around neurolaw? As well as writing fascinating science and philosophy-of-science

books such as Sum: Tales from the Afterlives and Incognito: The

Secret Lives of the Brain, neuroscientist David Eagleman spends a good deal of his time writing papers and speaking

on this subject. The truth of whether or not a person has committed a crime is

in the brain. The idea of trying to extract that truth by means other that the

traditional question-and-answer method is, however, ethically problematic to

say the least.

Rather than raising the

distressing prospect of courtroom psychosurgery, Eagleman tends to concentrate on the neuroscientifc facts

behind our concepts of blame and punishment: If we have little

choice in the ways our brains turn out, can we really be blamed and punished

when our actions cross the line, stepping from socially acceptable to socially

proscribed? In Incognito, he comes across as optimistic about the

future: ‘The upshot will be that we can have an evidence-based legal system in

which we will continue to take criminals off the streets, but we will change

our reasons for punishment and our opportunities for rehabilitation.’ He

also admits, however, that there are and will still be criminals for whom

neither punishment nor rehabilitation will succeed.

I have certain sympathies with

those who cry ‘neurobollocks!’ when writers and broadcasters attempt to dress

up thinly-informed neuron-gazing as true scientific insight. For example,

although I enjoyed it at the time, I now take Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink with

a hefty pinch of incredulity. Now what was his hypothesis again? That we are

really smart and usually right when we don’t think things through, and instead

just go with our ‘instincts’? Ponder the merit of that claim next time you end

up in a police cell after punching somebody in the face. It is perhaps not the

kind of self-help you were looking for.

It is also fair to say that the

bright lights of fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) have dazzled many.

Nuanced interpretations of what are, in reality, maps of blood flow in the

brain don’t make for exciting news stories.

But let us not be too hard on

those who try to frame every element of the human condition in cognitive terms.

It can be good for us to think that way. It can be truly humbling. In the

introduction to his book Connectome: How the Brain's

Wiring Makes Us Who We Are, Sebastian Seung puts it this way: ‘It is all of

these things. Indeed, sometimes I think it is everything.’ The wistful

sentiment bundled with that otherwise-austere statement touches me. Seung is

not circumscribing our potential; he is rejoicing in it, while acknowledging

its intricately fragile, self-referencing roots.

The blizzard of neuro-

neologisms will blow harder yet in the years to come. Some of its fall will

melt away; some will chill us to the cores of our being. An open mind does not

have to be a suggestible one. A healthy dose of scepticism may serve us well

during the great, surging neurostorm [sic] ahead.

No comments:

Post a Comment